Distributed learning

Distributed DQN (GORILA)

The main limitation of deep RL is the slowness of learning, which is mainly influenced by two factors:

- the sample complexity, i.e. the number of transitions needed to learn a satisfying policy.

- the online interaction with the environment (states are visited one after the other).

The second factor is particularly critical in real-world applications like robotics: physical robots evolve in real time, so the acquisition speed of transitions will be limited. Even in simulation (video games, robot emulators), the environment might turn out to be much slower than training the underlying neural network. In most settings, the value and target networks runs on a single GPu, while the environment is simulated on the CPU, as well as the ERM (there is not enough on the GPU to store it there). As the communication between the CPU and the GPU is rather slow, the GPU has to wait quite a long tme between two minibatches and is therefore idle most of the time.

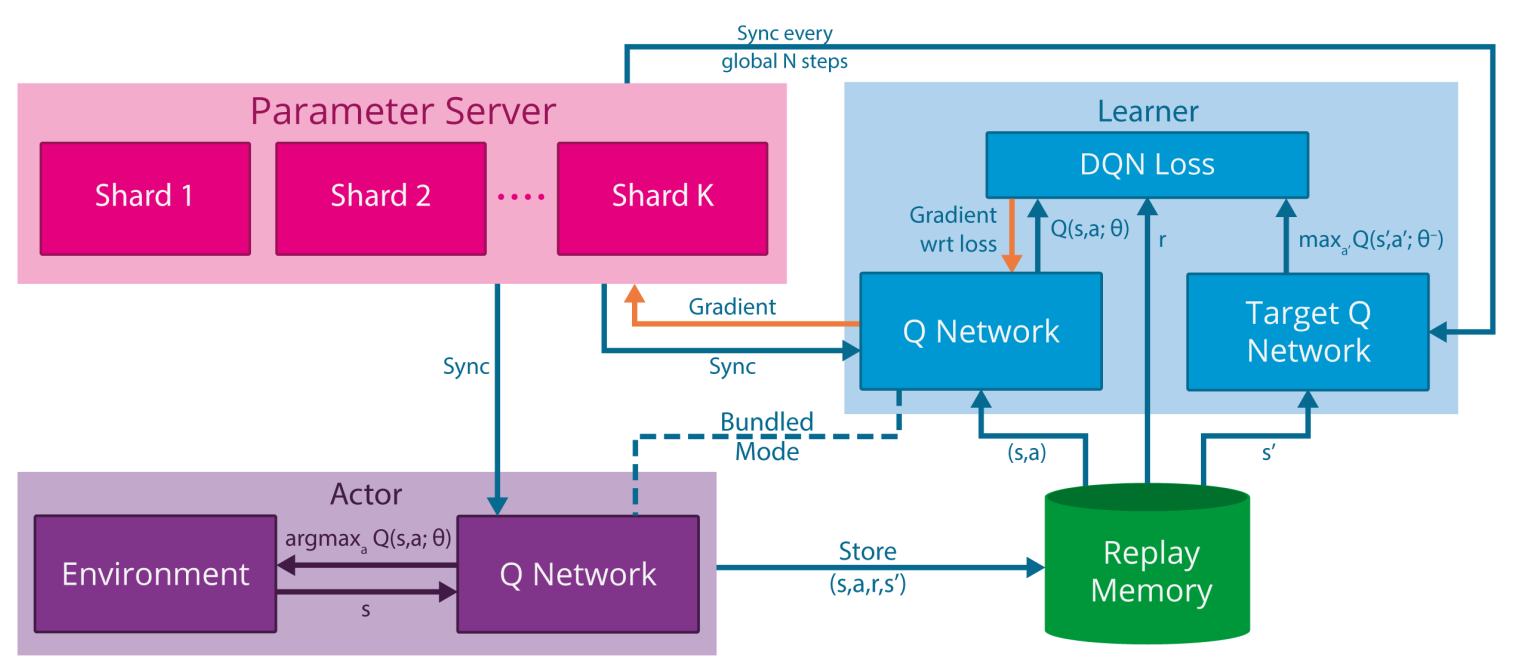

Google Deepmind proposed the GORILA (General Reinforcement Learning Architecture) framework to speed up the training of DQN networks using distributed actors and learners (Nair et al., 2015). The framework is quite general and the distribution granularity can change depending on the task.

In GORILA, multiple actors interact with the environment to gather transitions. Each actor has an independent copy of the environment, so they can gather N times more samples per second if there are N actors. This is possible in simulation (starting N instances of the same game in parallel) but much more complicated for real-world systems (but see Gu et al. (2017) for an example where multiple identical robots are used to gather experiences in parallel).

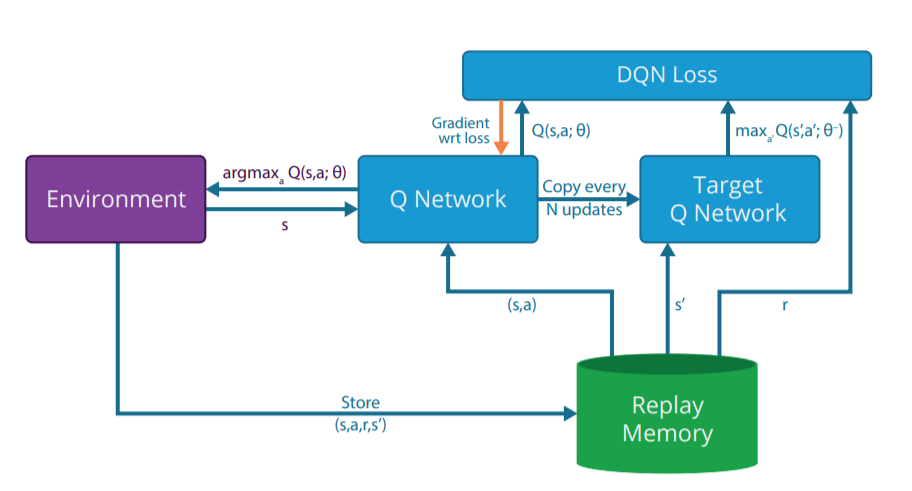

The experienced transitions are sent to the experience replay memory, which may be distributed or centralized. Multiple DQN learners will then sample a minibatch from the ERM and compute the DQN loss on this minibatch (also using a target network). All learners start with the same parameters \theta and simply compute the gradient of the loss function \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}(\theta)}{\partial \theta} on the minibatch. The gradients are sent to a parameter server (a master network) which uses the gradients to apply the optimizer (e.g. SGD) and find new values for the parameters \theta. Weight updates can also be applied in a distributed manner. This distributed method to train a network using multiple learners is now quite standard in deep learning: on multiple GPU systems, each GPU has a copy of the network and computes gradients on a different minibatch, while a master network integrates these gradients and updates the slaves.

The parameter server regularly updates the actors (to gather samples with the new policy) and the learners (to compute gradients w.r.t the new parameter values). Such a distributed system can greatly accelerate learning, but it can be quite tricky to find the optimum number of actors and learners (too many learners might degrade the stability) or their update rate (if the learners are not updated frequently enough, the gradients might not be correct).

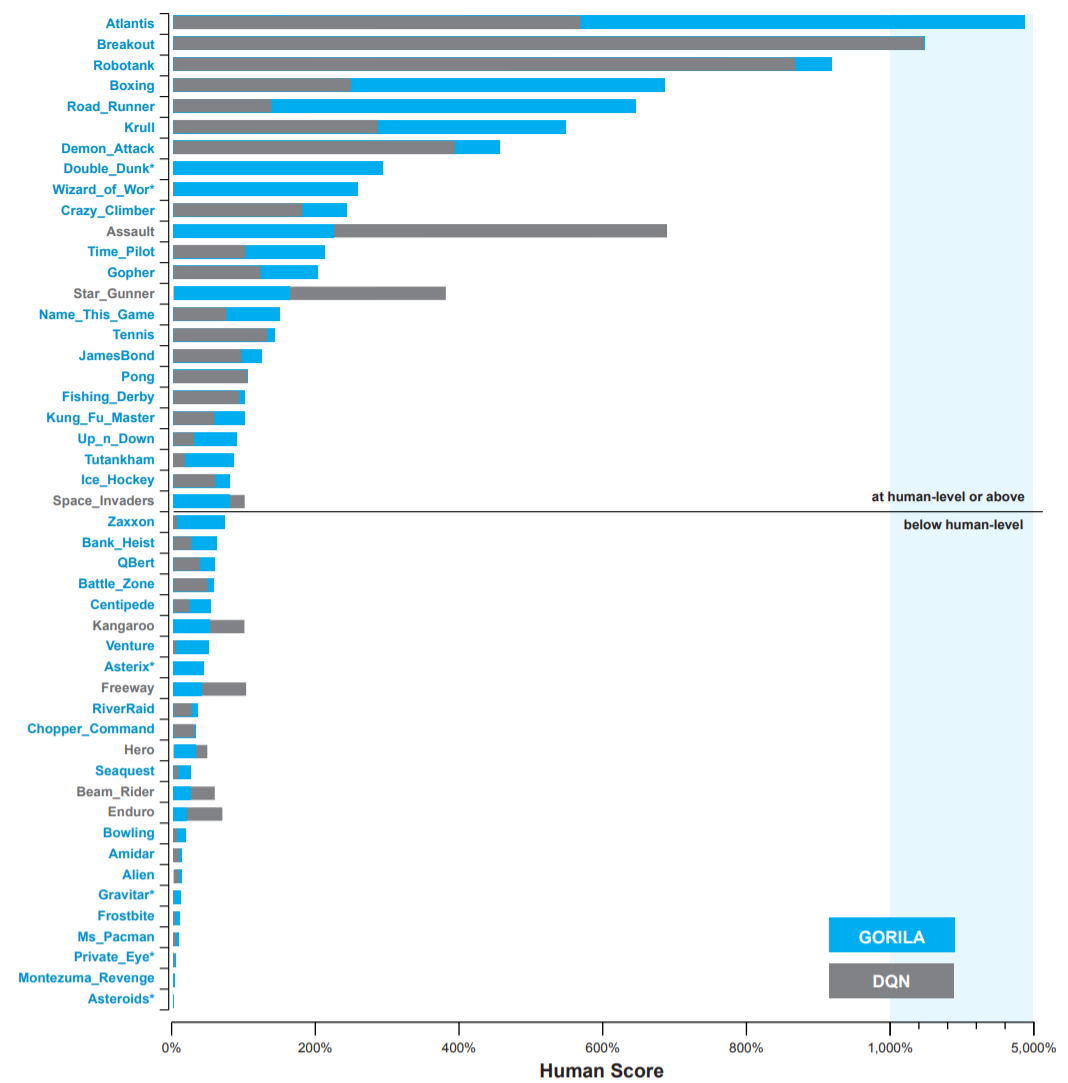

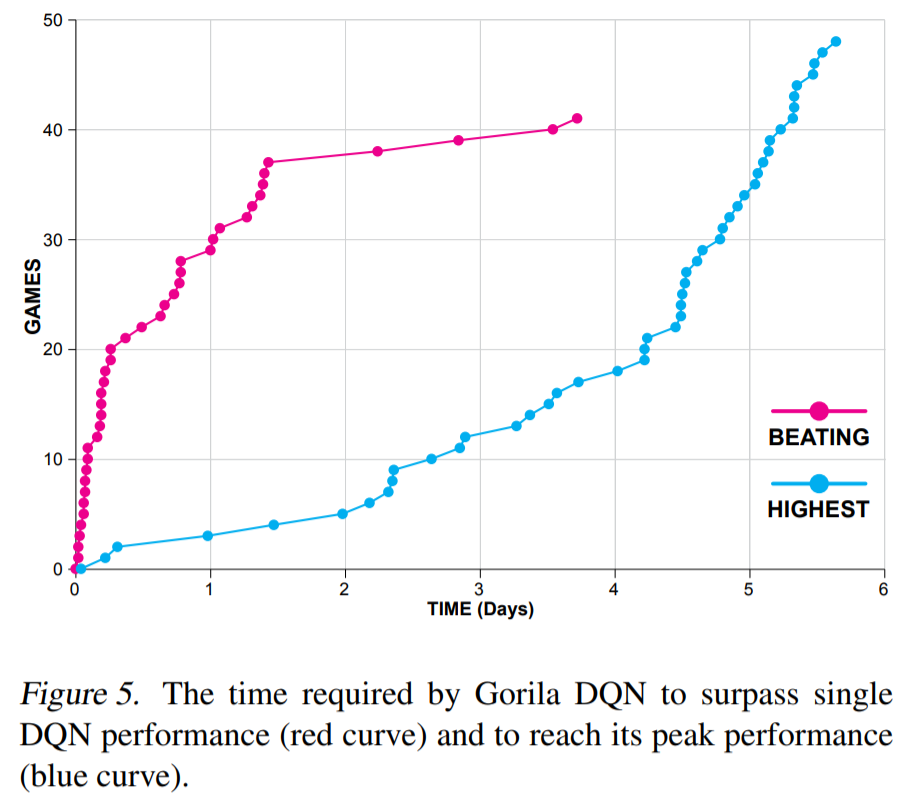

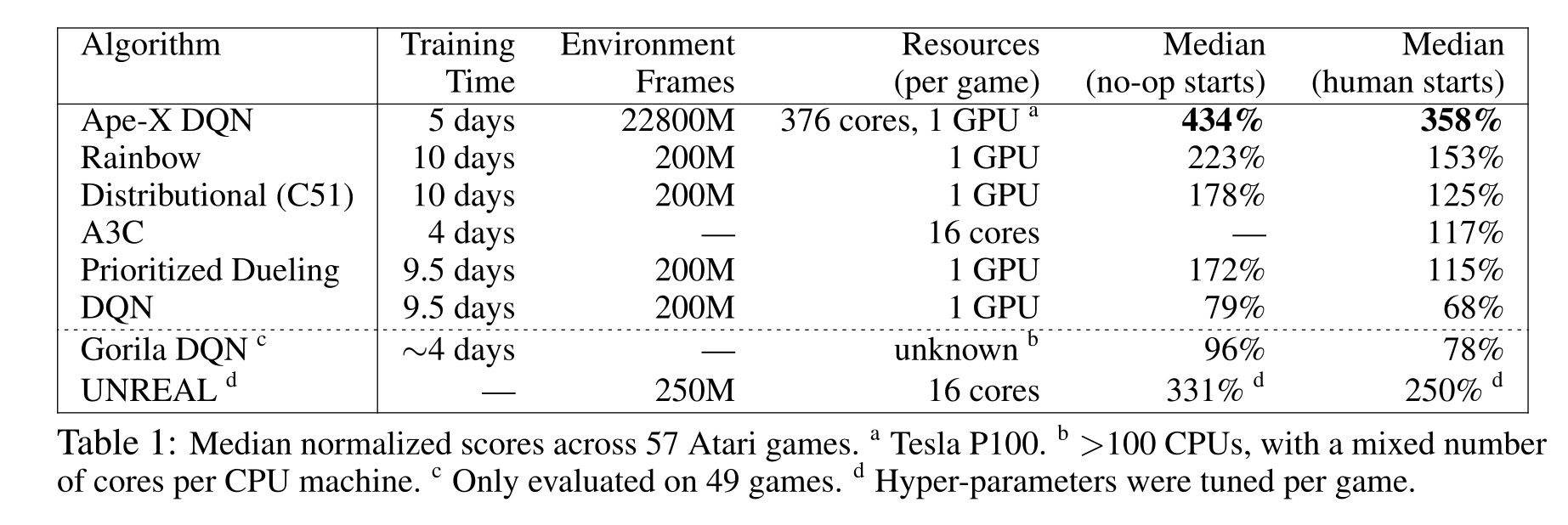

The final performance is not incredibly better than single-GPU DQN, but obtained much faster in wall-clock time (2 days instead of 12-14 days on a single GPU in 2015).

Ape-X

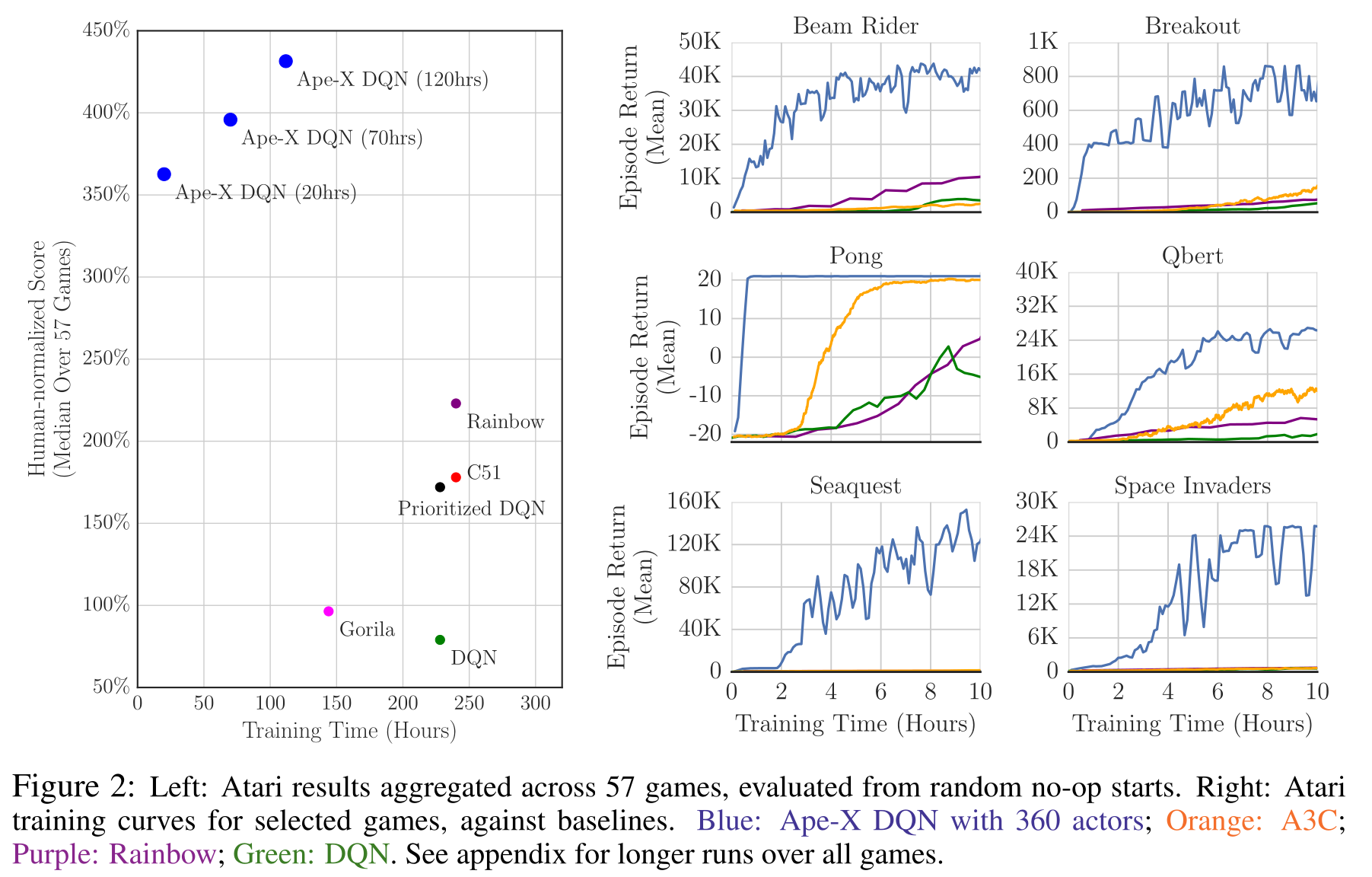

Further variants of distributed DQN learning include Ape-X (Horgan et al., 2018) and IMPALA (Espeholt et al., 2018). In Ape-X, they realized that using a single learner and many many actors is actually more efficient. The ERM further uses prioritized experience replay to increase the efficiency. The learner uses n-step returns and the double dueling DQN network architecture, so it is not much different from Rainbow DQN internally.

However, the multiple parallel workers can collect much more frames, leading to a much better performance in term of wall-clock time, but also pure performance (3x better than humans in only 20 hours of training, but using 360 CPU cores and one GPU).

Recurrent Replay Distributed DQN (R2D2)

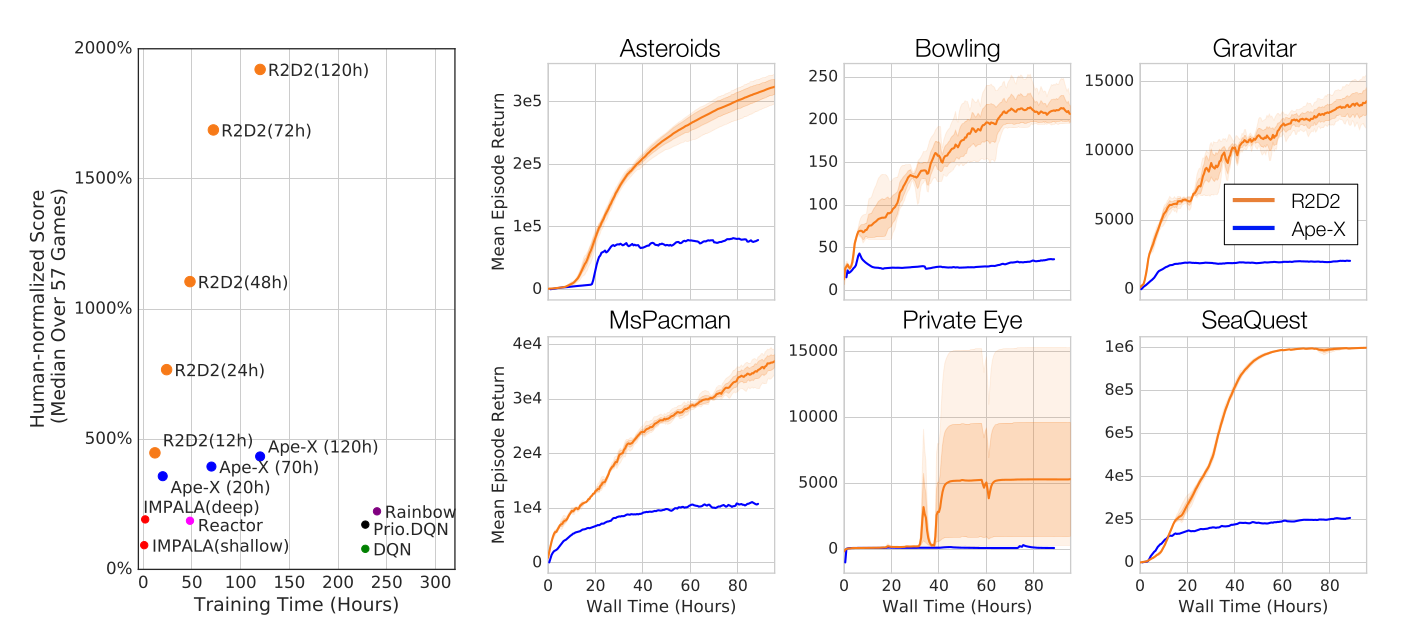

R2D2 (Kapturowski et al., 2019) builds on Ape-X and DRQN by combining:

- a double dueling DQN with n-step returns (n=5) and prioritized experience replay.

- 256 CPU actors, 1 GPU learner for distributed learning.

- a LSTM layer after the convolutional stack to address POMDPs.

Additionally solving practical problems with LSTMs (choice of the initial state), it became for a moment the state of the art on the Atari-57 benchmark. The jump in performance from Ape-X is impressive. Distributed learning with multiple actor is now a standard technique, as it only necessitates a few more cores (or robots…).