1. Optimization¶

Slides: pdf

1.1. Analytic optimization¶

Machine learning is all about optimization:

Supervised learning minimizes the error between the prediction and the data.

Unsupervised learning maximizes the fit between the model and the data

Reinforcement learning maximizes the collection of rewards.

The function to be optimized is called the objective function, cost function or loss function. ML searches for the value of free parameters which optimize the objective function on the data set. The simplest optimization method is the gradient descent (or ascent) method.

The easiest method to find the optima of a function \(f(x)\) is to look where its first-order derivative is equal to 0:

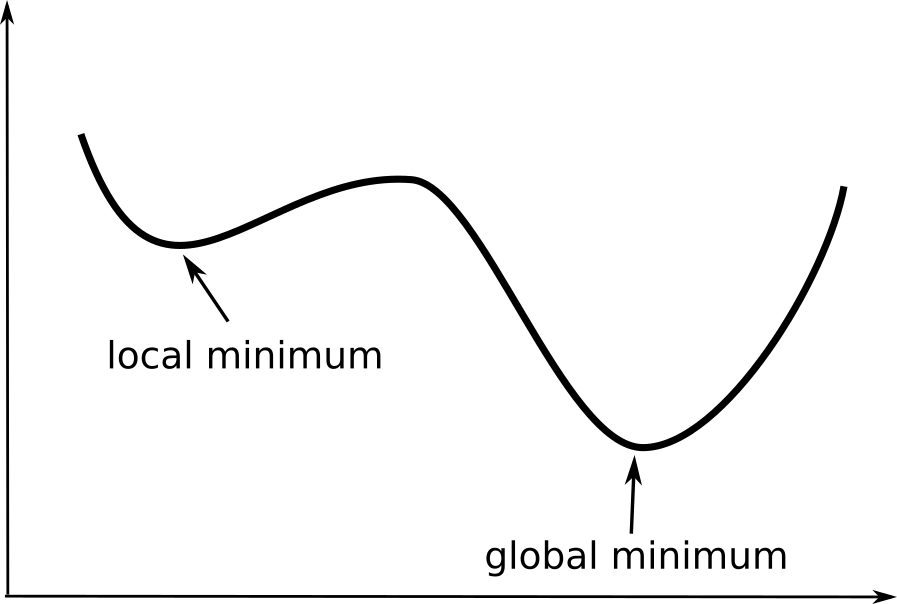

The sign of the second order derivative tells us whether it is a maximum or minimum. There can be multiple minima or maxima (or none) depending on the function. The “best” minimum (with the lowest value among all minima) is called the global minimum. The others are called local minima.

Fig. 1.16 Functions (may) have one global minimum but several local minima.¶

Multivariate functions

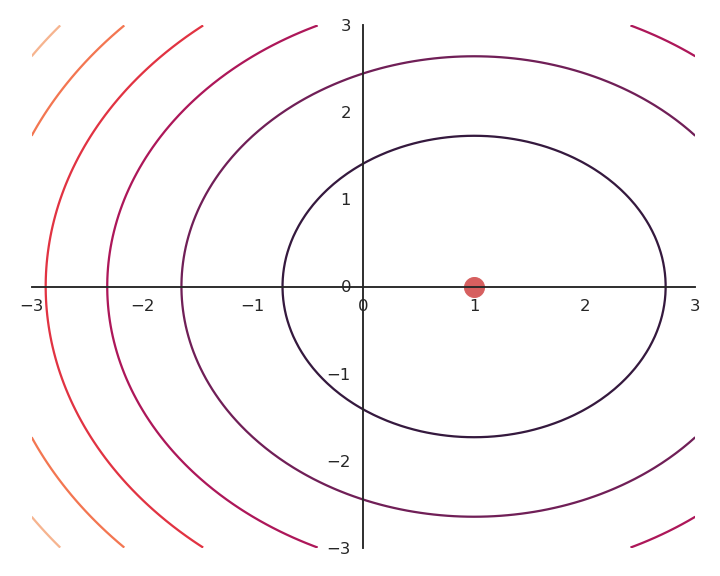

A multivariate function is a function of more than one variable, e.g. \(f(x, y)\). A point \((x^*, y^*)\) is an optimum of \(f\) if all partial derivatives are zero:

The vector of partial derivatives is called the gradient of the function:

Fig. 1.17 Multivariate optimization of \(f(x, y) = (x - 1)^2 + y^2 + 1\). The minimum is in \((1, 0)\).¶

1.2. Gradient descent¶

In machine learning, we generally do not have access to the analytical form of the objective function. We can not therefore get its derivative and search where it is 0. However, we have access to its value (and derivative) for certain values, for example:

We can “ask” the model for as many values as we want, but we never get its analytical form. For most useful problems, the function would be too complex to differentiate anyway.

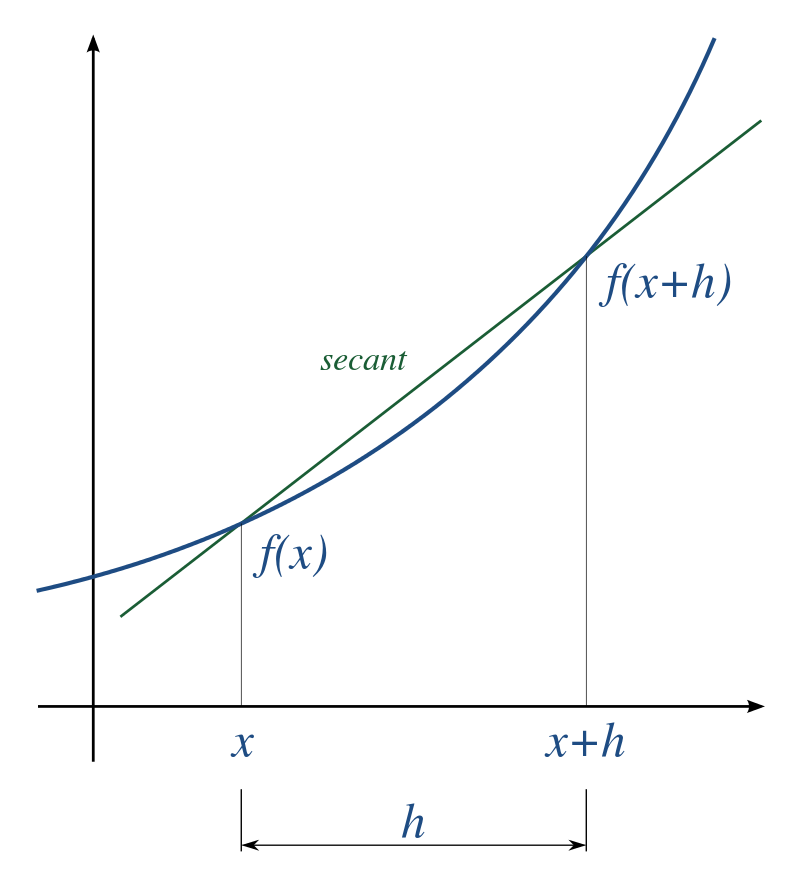

Fig. 1.18 Euler method: the derivative of a function is the slope of its tangent.¶

Let’s remember the definition of the derivative of a function. The derivative \(f'(x)\) is defined by the slope of the tangent of the function:

If we take \(h\) small enough, we have the following approximation:

If we want \(x+h\) to be closer to the minimum than \(x\), we want:

or:

We therefore want that:

The change \(h\) in the value of \(x\) must have the opposite sign of \(f'(x)\) in order to get closer to the minimum. If the function is increasing in \(x\), the minimum is smaller (to the left) than \(x\). If the function is decreasing in \(x\), the minimum is bigger than \(x\) (to the right).

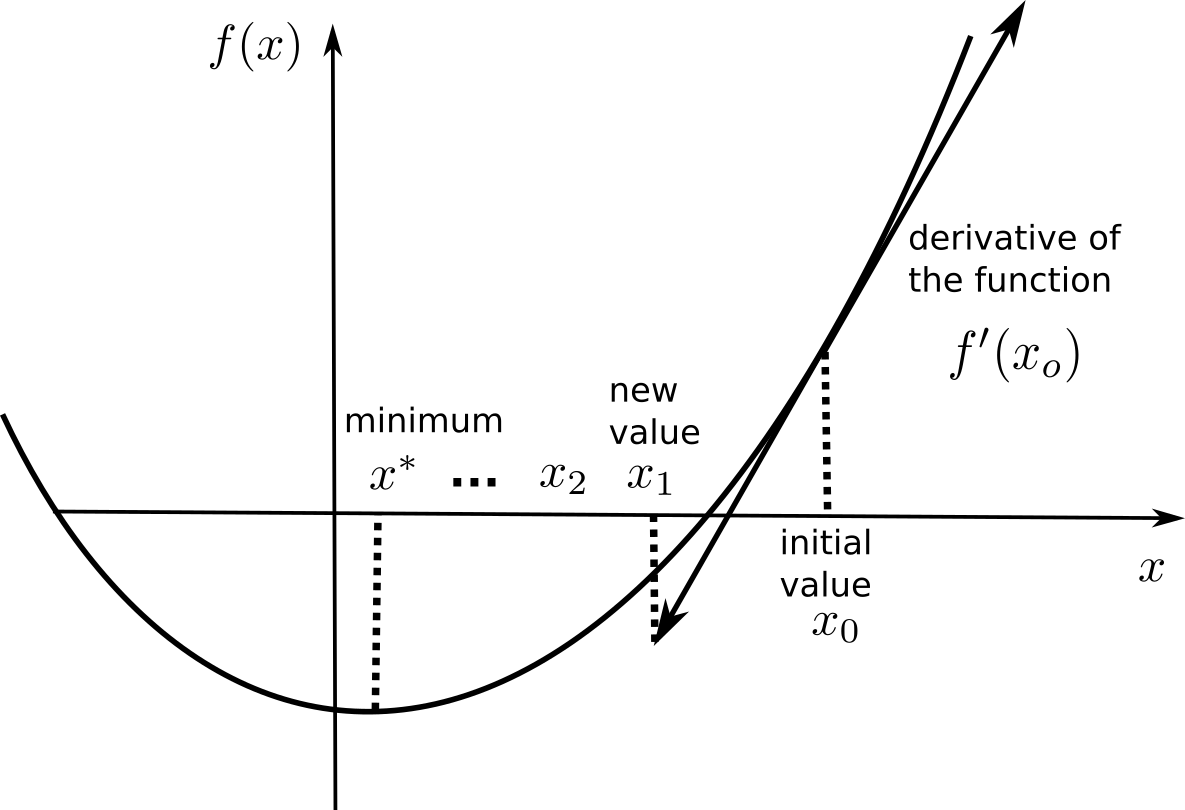

Gradient descent (GD) is a first-order method to iteratively find the minimum of a function \(f(x)\). It starts with a random estimate \(x_0\) and iteratively changes its value so that it becomes closer to the minimum.

Fig. 1.19 Gradient descent iteratively modifies the estimate \(x_n\) in the opposite direction of the derivative.¶

It creates a series of estimates \([x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots]\) that converge to a local minimum of \(f\). Each element of the series is calculated based on the previous element and the derivative of the function in that element:

If the function is locally increasing (resp. decreasing), the new estimate should be smaller (resp. bigger) than the previous one. \(\eta\) is a small parameter between 0 and 1 called the learning rate that controls the speed of convergence (more on that later).

Gradient descent algorithm:

We start with an initially wrong estimate of \(x\): \(x_0\)

for \(n \in [0, \infty]\):

We compute or estimate the derivative of the loss function in \(x_{n}\): \(f'(x_{n})\)

We compute a new value \(x_{n+1}\) for the estimate using the gradient descent update rule:

\[ \Delta x = x_{n+1} - x_n = - \eta \, f'(x_n) \]

There is theoretically no end to the GD algorithm: we iterate forever and always get closer to the minimum. The algorithm can be stopped when the change \(\Delta x\) is below a threshold.

Fig. 1.20 Visualization of Gradient Descent on a quadratic function. Notice how the speed of convergence slows down when approaching the minimum.¶

Gradient descent can be applied to multivariate functions:

Each variable is updated independently using partial derivatives:

We can also use the vector notation to use the gradient operator:

The change in the estimation is in the opposite direction of the gradient, hence the name gradient descent.

Fig. 1.21 Visualization of Gradient Descent on a multivariate function in 2 dimensions.¶

The choice of the learning rate \(\eta\) is critical:

If it is too small, the algorithm will need a lot of iterations to converge.

If it is too big, the algorithm can oscillate around the desired values without ever converging.

Fig. 1.22 Influence of the learning on convergence: too small (red) and it takes forever, too high (green) and convergence is unstable. Finding its optimal value (blue) is hard as it depends on the function itself.¶

Gradient descent is not optimal: it always finds a local minimum, but there is no guarantee that it is the global minimum. The found solution depends on the initial choice of \(x_0\). If you initialize the parameters near to the global minimum, you are lucky. But how? This will be a big issue in neural networks.

1.3. Regularization¶

1.3.1. L2 - Regularization¶

Most of the time, there are many minima to a function, if not an infinity. As GD only converges to the “closest” local minimum, you are never sure that you get a good solution. Consider the following function:

As it does not depend on \(y\), whatever initial value \(y_0\) will be considered as a solution. As we will see later, this is something we do not want.

Fig. 1.23 Function with an infinity of minima: as long as \(x=1\), each point on the vertical line is a minimum.¶

To obtain a single solution, we may want to put the additional constraint that both \(x\) and \(y\) should be as small as possible. One possibility is to also minimize the Euclidian norm (or L2-norm) of the vector \(\mathbf{x} = [x, y]\).

Note that this objective is in contradiction with the original objective: \((0, 0)\) minimizes the norm, but not the function \(f(x, y)\). We construct a new function as the sum of \(f(x, y)\) and the norm of \(\mathbf{x}\), weighted by the regularization parameter \(\lambda\):

For a fixed value of \(\lambda\) (for example 0.1), we now minimize using gradient descent this new loss function. To do that, we just need to compute its gradient:

and apply gradient descent iteratively:

Fig. 1.24 Gradient descent with L2 regularization, using \(\lambda = 0.1\).¶

You may notice that the result of the optimization is a bit off, it is not exactly \((1, 0)\). This is because we do not optimize \(f(x, y)\) directly, but \(\mathcal{L}(x, y)\). Let’s have a look at the landscape of the loss function:

Fig. 1.25 Landscape of the loss function \(\mathcal{L}(x, y) = f(x, y) + \lambda \, (x^2 + y^2)\) with \(\lambda = 0.1\).¶

The optimization with GD indeed works, it is just that the function is different. The constraint on the Euclidian norm “attracts” or “distorts” the function towards \((0, 0)\). This may seem counter-intuitive, but we will see with deep networks that we can live with it. Let’s now look at what happens when we increase \(\lambda\) to 5:

Fig. 1.26 Gradient descent with L2 regularization, using \(\lambda = 5\).¶

Fig. 1.27 Landscape of the loss function \(\mathcal{L}(x, y) = f(x, y) + \lambda \, (x^2 + y^2)\) with \(\lambda = 5\).¶

Now the result of the optimization is totally wrong: the constraint on the norm completely dominates the optimization process.

\(\lambda\) controls which of the two objectives, \(f(x, y)\) or \(x^2 + y^2\), has the priority:

When \(\lambda\) is small, \(f(x, y)\) dominates and the norm of \(\mathbf{x}\) can be anything.

When \(\lambda\) is big, \(x^2 + y^2\) dominates, the result will be very small but \(f(x, y)\) will have any value.

The right value for \(\lambda\) is hard to find. We will see later methods to experimentally find its most adequate value.

Note

Regularization is a form of constrained optimization. What we actually want to solve is the constrained optimization problem:

i.e. minimize \(f(x, y)\) while keeping the norm of \([x, y]\) below a threshold \(\delta\). Lagrange optimization (technically KKT optimization; see the course Introduction to AI) allows to solve that problem by searching the minimum of the generalized Lagrange function:

Regularization is a special case of Lagrange optimization, as it considers \(\lambda\) to be fixed, while it is an additional variable in Lagrange optimization. When differentiating this function, \(\delta\) disappears anyway, so it is equivalent to our regularized loss function.

1.3.2. L1 - Regularization¶

Another form of regularization is L1 - regularization using the L1-norm (absolute values):

Its gradient only depend on the sign of \(x\) and \(y\):

It tends to lead to sparser value of \((x, y)\), i.e. either \(x\) or \(y\) will be close or equal to 0.

Fig. 1.28 Gradient descent with L1 regularization, using \(\lambda = 0.1\).¶

Both L1 and L2 regularization can be used in neural networks depending on the desired effect.