3. Convolutional neural networks¶

Slides: pdf

3.1. Convolutional neural networks¶

3.1.1. Rationale¶

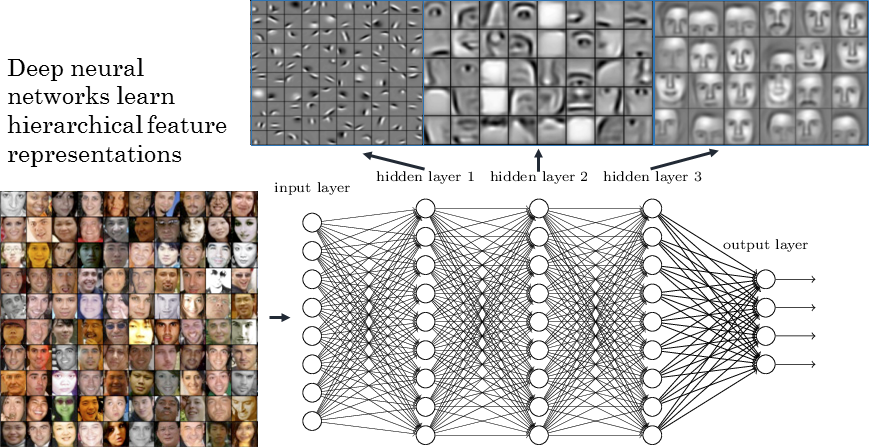

The different layers of a deep network extract increasingly complex features.

edges \(\rightarrow\) contours \(\rightarrow\) shapes \(\rightarrow\) objects

Using full images as inputs leads to an explosion of the number of weights to be learned: A moderately big 800 * 600 image has 480,000 pixels with RGB values. The number of dimensions of the input space is 800 * 600 * 3 = 1.44 million. Even if you take only 1000 neurons in the first hidden layer, you get 1.44 billion weights to learn, just for the first layer. To obtain a generalization error in the range of 10%, you would need at least 14 billion training examples…

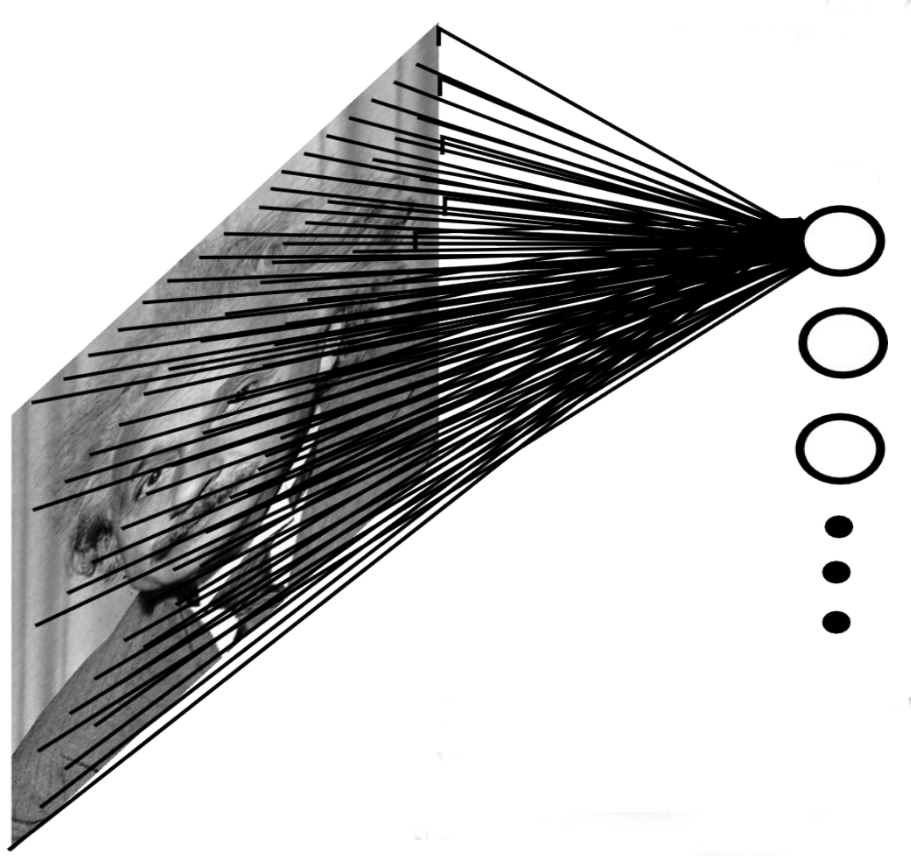

Fig. 3.40 Fully-connected layers require a lot of weights in images.¶

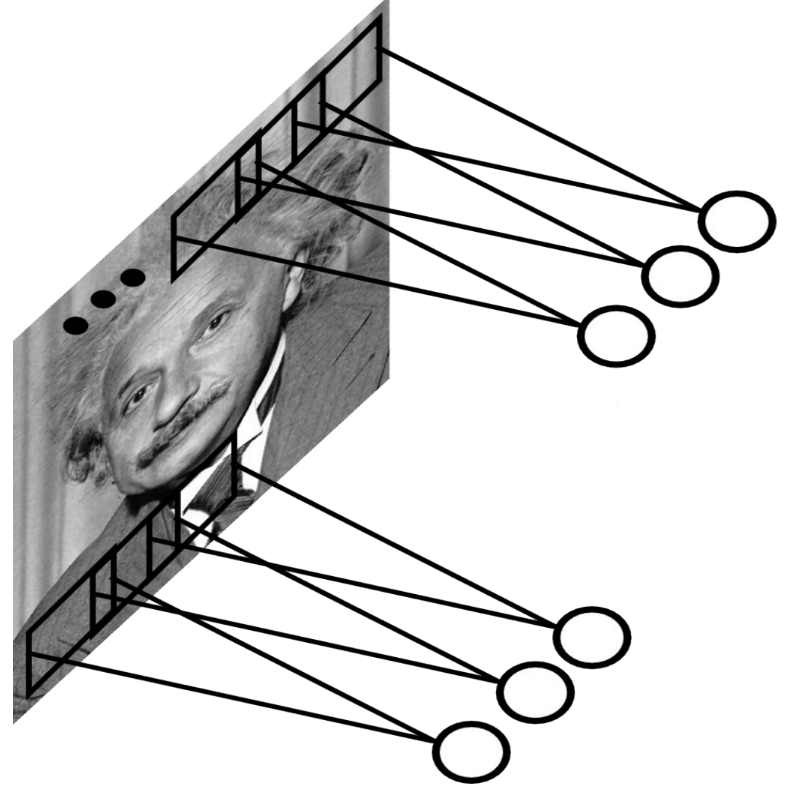

Early features (edges) are usually local, there is no need to learn weights from the whole image. Natural images are stationary: the statistics of the pixel in a small patch are the same, regardless the position on the image. Idea: One only needs to extract features locally and share the weights between the different locations. This is a convolution operation: a filter/kernel is applied on small patches and slided over the whole image.

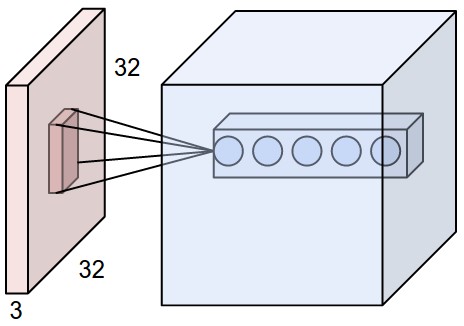

Fig. 3.41 Convolutional layers share weights along the image dimensions.¶

3.1.2. The convolutional layer¶

Fig. 3.42 Principle of a convolution. Source: https://towardsdatascience.com/a-comprehensive-guide-to-convolutional-neural-networks-the-eli5-way-3bd2b1164a53¶

In a convolutional layer, \(d\) filters are defined with very small sizes (3x3, 5x5…). Each filter is convoluted over the input image (or the previous layer) to create a feature map. The set of \(d\) feature maps becomes a new 3D structure: a tensor.

Fig. 3.43 Convolutional layer. Source: http://cs231n.github.io/convolutional-networks/¶

If the input image is 32x32x3, the resulting tensor will be 32x32xd. The convolutional layer has only very few parameters: each feature map has 3x3x3 values in the filter plus a bias, i.e. 28 parameters. As in image processing, a padding method must be chosen (what to do when a pixel is outside the image).

Fig. 3.44 Convolution with stride 1. Source: https://github.com/vdumoulin/conv_arithmetic¶

3.1.3. Max-pooling layer¶

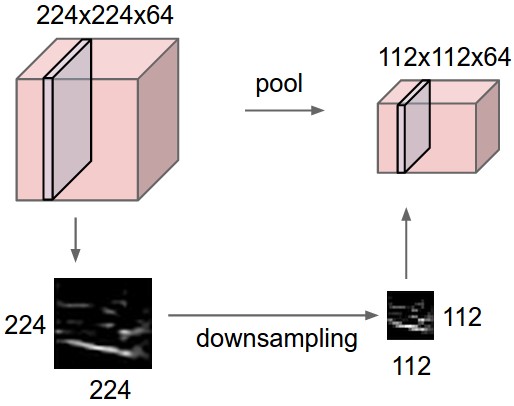

The number of elements in a convolutional layer is still too high. We need to reduce the spatial dimension of a convolutional layer by downsampling it. For each feature, a max-pooling layer takes the maximum value of a feature for each subregion of the image (generally 2x2).Mean-pooling layers are also possible, but they are not used anymore. Pooling allows translation invariance: the same input pattern will be detected whatever its position in the input image.

Fig. 3.45 Pooling layer. Source: http://cs231n.github.io/convolutional-networks/¶

Fig. 3.46 Pooling layer. Source: http://cs231n.github.io/convolutional-networks/¶

3.1.4. Convolution with strides¶

Convolution with strides [Springenberg et al., 2015] is an alternative to max-pooling layers. The convolution simply “jumps” one pixel when sliding over the image (stride 2). This results in a smaller feature map, using much less operations than a convolution with stride 1 followed by max-pooling, for the same performance. They are particularly useful for generative models (VAE, GAN, etc).

Fig. 3.47 Convolution with stride 2. Source: https://github.com/vdumoulin/conv_arithmetic¶

3.1.5. Dilated convolutions¶

A dilated convolution is a convolution with holes (à trous). The filter has a bigger spatial extent than its number of values.

Fig. 3.48 Convolution à trous. Source: https://github.com/vdumoulin/conv_arithmetic¶

3.1.6. Backpropagation through a convolutional layer¶

But how can we do backpropagation through a convolutional layer?

Fig. 3.49 Forward convolution. Source: https://medium.com/@mayank.utexas/backpropagation-for-convolution-with-strides-8137e4fc2710¶

In the example above, the four neurons of the feature map will receive a gradient from the upper layers. How can we use it to learn the filter values and pass the gradient to the lower layers?

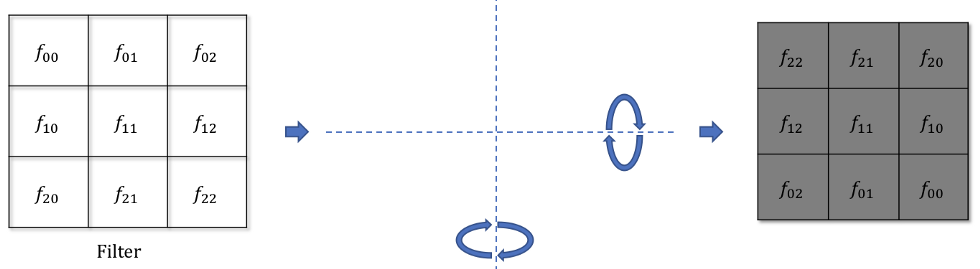

The answer is simply by convolving the output gradients with the flipped filter!

Fig. 3.50 Backward convolution. Source: https://medium.com/@mayank.utexas/backpropagation-for-convolution-with-strides-8137e4fc2710¶

The filter just has to be flipped (\(180^o\) symmetry) before the convolution.

Fig. 3.51 Flipping the filter. Source: https://medium.com/@mayank.utexas/backpropagation-for-convolution-with-strides-8137e4fc2710¶

The convolution operation is differentiable, so we can apply backpropagation and learn the filters.

3.1.7. Backpropagation through a max-pooling layer¶

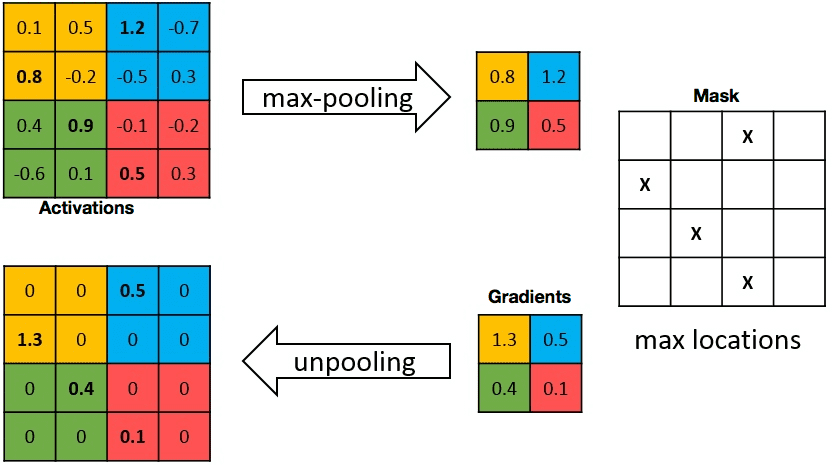

We can also use backpropagation through a max-pooling layer. We need to remember which location was the winning location in order to backpropagate the gradient. A max-pooling layer has no parameter, we do not need to learn anything, just to pass the gradient backwards.

Fig. 3.52 Backpropagation through a max-pooling layer. Source: https://mukulrathi.com/demystifying-deep-learning/conv-net-backpropagation-maths-intuition-derivation/¶

3.1.8. Convolutional Neural Networks¶

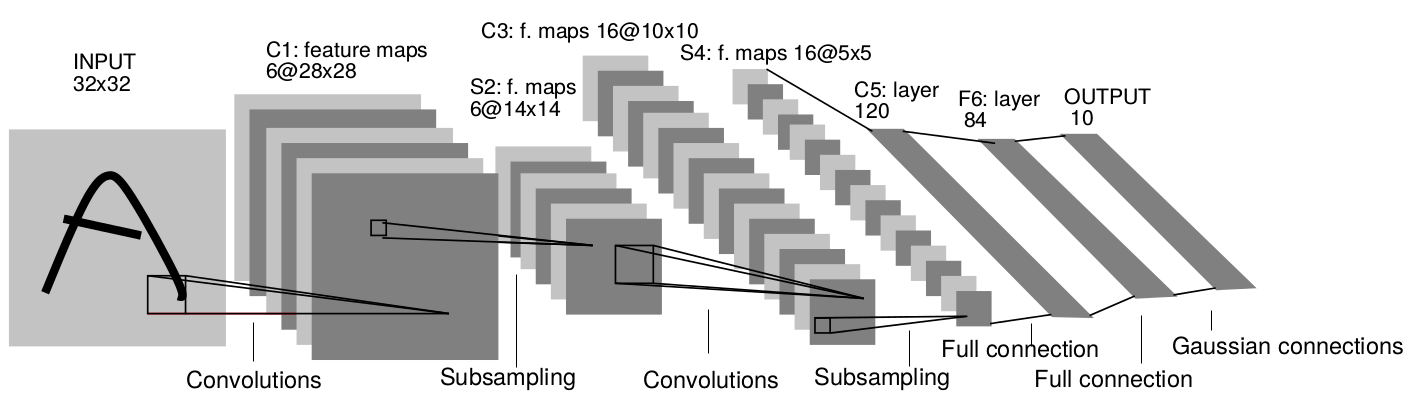

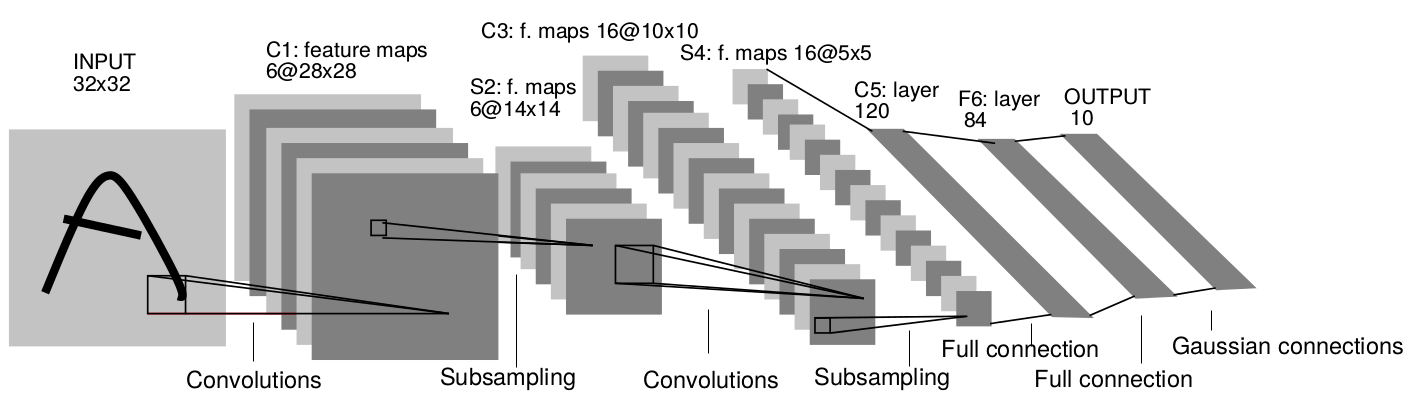

A convolutional neural network (CNN) is a cascade of convolution and pooling operations, extracting layer by layer increasingly complex features. The spatial dimensions decrease after each pooling operation, but the number of extracted features increases after each convolution. One usually stops when the spatial dimensions are around 7x7. The last layers are fully connected (classical MLP). Training a CNN uses backpropagation all along: the convolution and pooling operations are differentiable.

Fig. 3.53 Convolutional Neural Network. [LeCun et al., 1998].¶

Implementing a CNN in keras

Convolutional and max-pooling layers are regular objects in keras/tensorflow/pytorch/etc. You do not need to care about their implementation, they are designed to run fast on GPUs. You have to apply to the CNN all the usual tricks: optimizers, dropout, batch normalization, etc.

model = Sequential()

model.add(Input(X_train.shape[1:]))

model.add(Conv2D(32, (3, 3), padding='same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Conv2D(32, (3, 3)))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(Dropout(0.25))

model.add(Conv2D(64, (3, 3), padding='same'))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Conv2D(64, (3, 3)))L

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(Dropout(0.25))

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(512))

model.add(Activation('relu'))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

model.add(Dense(num_classes))

model.add(Activation('softmax'))

opt = RMSprop(

lr=0.0001,

decay=1e-6

)

model.compile(

loss='categorical_crossentropy',

optimizer=opt,

metrics=['accuracy']

)

3.2. Some famous convolutional networks¶

3.2.1. Neocognitron¶

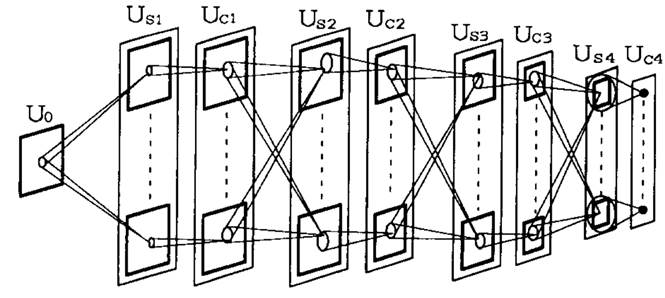

The Neocognitron (Fukushima, 1980 [Fukushima, 1980]) was actually the first CNN able to recognize handwritten digits. Training is not based on backpropagation, but a set of biologically realistic learning rules (Add-if-silent, margined WTA). Inspired by the human visual system.

Fig. 3.54 Neocognitron. [Fukushima, 1980]. Source: https://uplLoad.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/uk/4/42/Neocognitron.jpg¶

3.2.2. LeNet¶

LeNet (1998, Yann LeCun at AT&T labs [LeCun et al., 1998]) was one of the first CNN able to learn from raw data using backpropagation. It has two convolutional layers, two mean-pooling layers, two fully-connected layers and an output layer. It uses tanh as the activation function and works on CPU only. Used for handwriting recognition (for example ZIP codes).

Fig. 3.55 LeNet5. [LeCun et al., 1998].¶

3.2.3. AlexNet¶

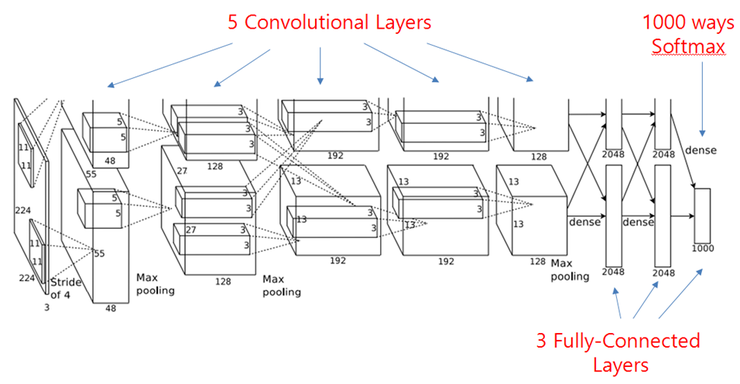

AlexNet (2012, Toronto University [Krizhevsky et al., 2012]) started the DL revolution by winning ImageNet 2012. I has a similar architecture to LeNet, but is trained on two GPUs using augmented data. It uses ReLU, max-pooling, dropout, SGD with momentum, L2 regularization.

Fig. 3.56 Alexnet [Krizhevsky et al., 2012].¶

3.2.4. VGG-16¶

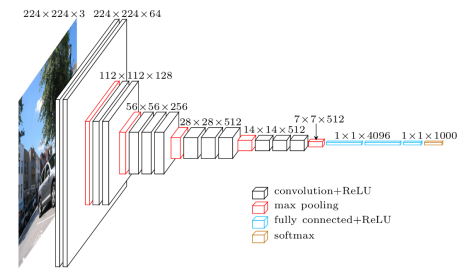

VGG-16 (2014, Visual Geometry Group, Oxford [Simonyan & Zisserman, 2015]) placed second at ImageNet 2014. It went much deeper than AlexNet with 16 parameterized layers (a VGG-19 version is also available with 19 layers). Its main novelty is that two convolutions are made successively before the max-pooling, implicitly increasing the receptive field (2 consecutive 3x3 filters cover 5x5 pixels). Drawback: 140M parameters (mostly from the last convolutional layer to the first fully connected) quickly fill up the memory of the GPU.

Fig. 3.57 VGG-16 [Simonyan & Zisserman, 2015].¶

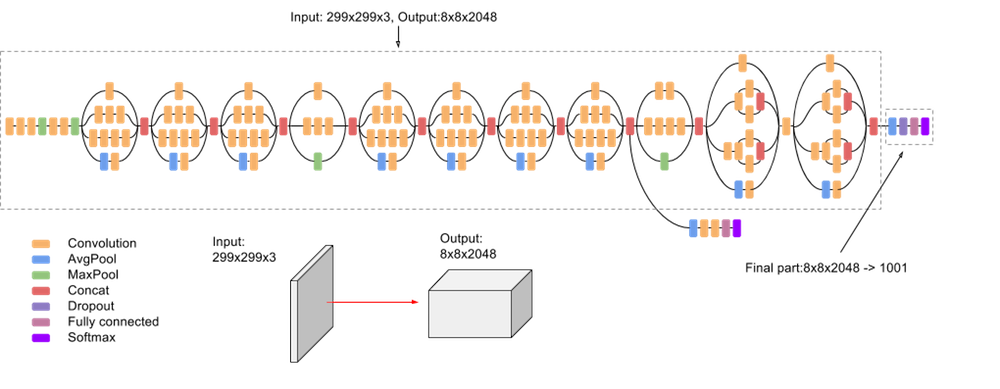

3.2.5. GoogLeNet - Inception v1¶

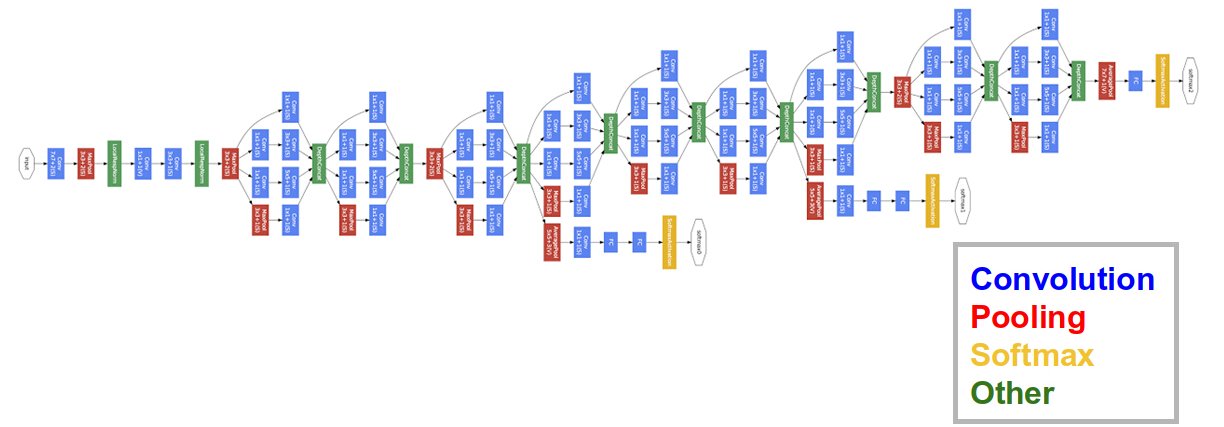

GoogLeNet (2014, Google Brain [Szegedy et al., 2015]) used Inception modules (Network-in-Network) to further complexify each stage It won ImageNet 2014 with 22 layers. Dropout, SGD with Nesterov momentum.

Fig. 3.58 GoogLeNet [Szegedy et al., 2015].¶

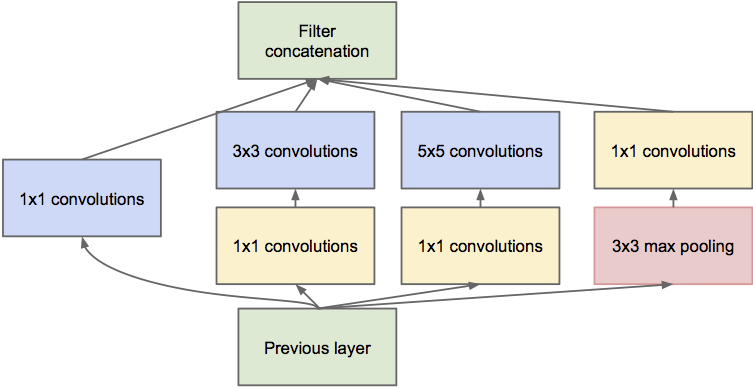

Inside GoogleNet, each Inception module learns features at different resolutions using convolutions and max poolings of different sizes. 1x1 convolutions are shared MLPS: they transform a \((w, h, d_1)\) tensor into \((w, h, d_2)\) pixel per pixel. The resulting feature maps are concatenated along the feature dimension and passed to the next module.

Fig. 3.59 Inception module [Szegedy et al., 2015].¶

Three softmax layers predict the classes at different levels of the network. The combined loss is:

Only the deeper softmax layer matters for the prediction. The additional losses improve convergence by fight vanishing gradients: the early layers get useful gradients from the lower softmax layers.

Several variants of GoogleNet have been later proposed: Inception v2, v3, InceptionResNet, Xception… Xception [Chollet, 2017b] has currently the best top-1 accuracy on ImageNet: 126 layers, 22M parameters (88 MB). Pretrained weights are available in keras:

tf.keras.applications.Xception(include_top=True, weights="imagenet")

Fig. 3.60 Inception v3 [Chollet, 2017b]. Source: https://cloud.google.com/tpu/docs/inception-v3-advanced¶

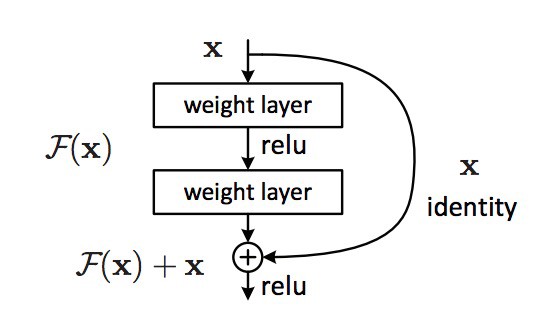

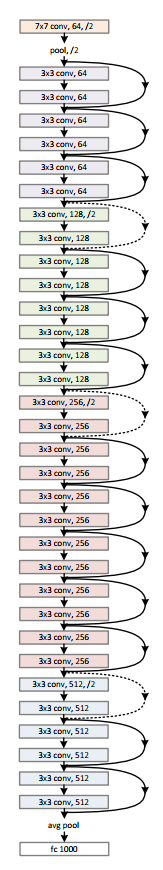

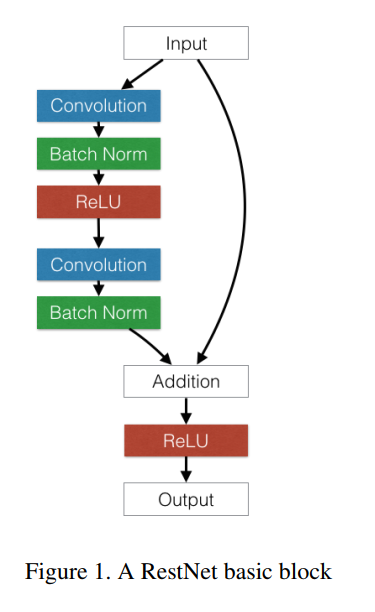

3.2.6. ResNet¶

ResNet (2015, Microsoft [He et al., 2015a]) won ImageNet 2015. Instead of learning to transform an input directly with \(\mathbf{h}_n = f_W(\mathbf{h}_{n-1})\), a residual layer learns to represent the residual between the output and the input:

Fig. 3.61 Residual layer with skip connections [He et al., 2015a].¶

These skip connections allow the network to decide how deep it has to be. If the layer is not needed, the residual layer learns to output 0.

Fig. 3.62 ResNet [He et al., 2015a].¶

Skip connections help overcome the vanishing gradients problem, as the contribution of bypassed layers to the backpropagated gradient is 1.

The norm of the gradient stays roughly around one, limiting vanishing. Skip connections even can bypass whole blocks of layers. ResNet can have many layers without vanishing gradients. The most popular variants are:

ResNet-50.

ResNet-101.

ResNet-152.

It was the first network to make an heavy use of batch normalization.

Fig. 3.63 Residual block [He et al., 2015a].¶

3.2.7. HighNets: Highway networks¶

Highway networks (IDSIA [Srivastava et al., 2015]) are residual networks which also learn to balance inputs with feature extraction:

The balance between the primary pathway and the skip pathway adapts to the task. It has been used up to 1000 layers and improved state-of-the-art accuracy on MNIST and CIFAR-10.

Fig. 3.64 Highway network [Srivastava et al., 2015].¶

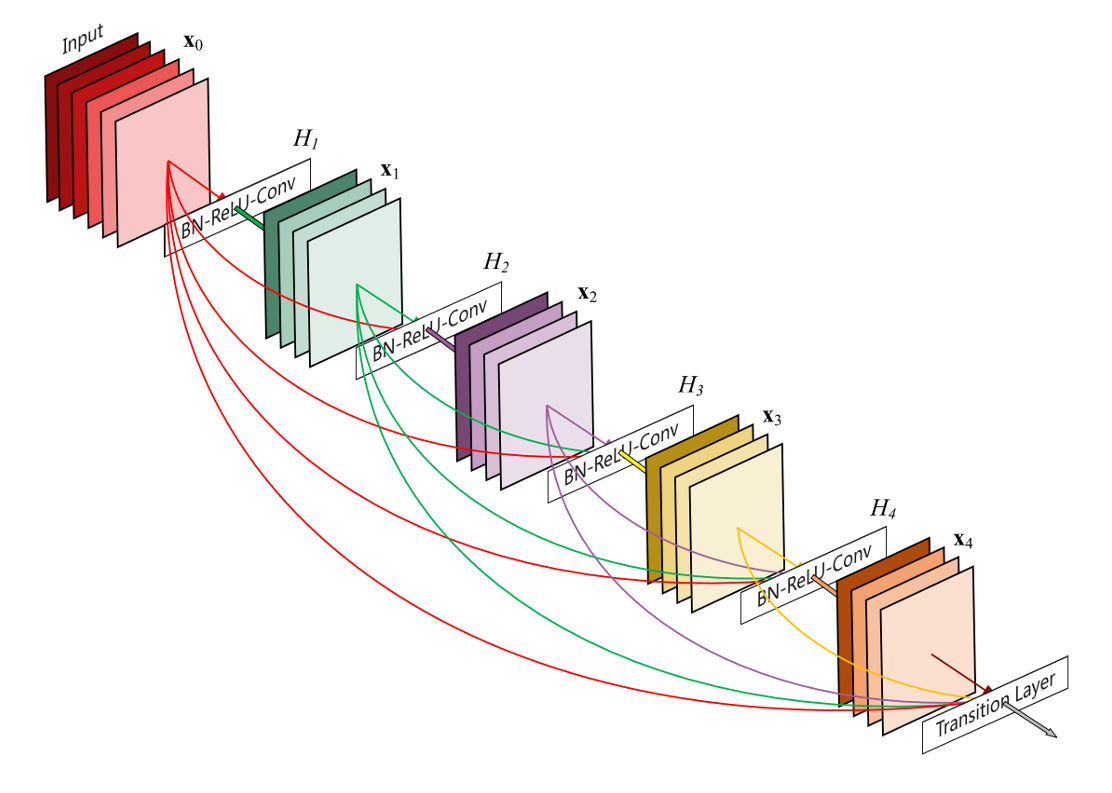

3.2.8. DenseNets: Dense networks¶

Dense networks (Cornell University & Facebook AI [Huang et al., 2018]) are residual networks that can learn bypasses between any layer of the network (up to 5). It has 100 layers altogether and improved state-of-the-art accuracy on five major benchmarks.

Fig. 3.65 Dense network [Huang et al., 2018].¶

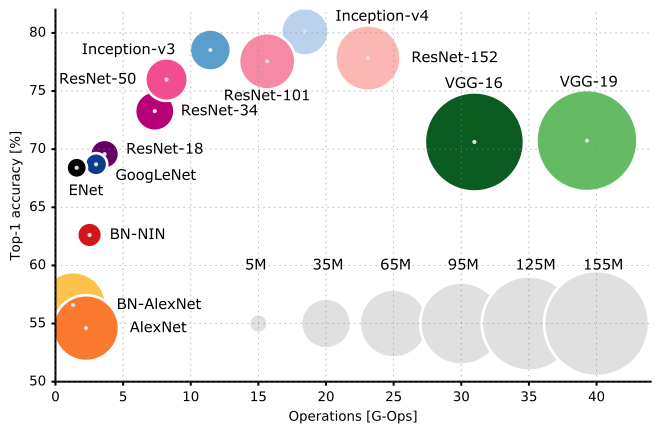

3.2.9. Model zoos¶

These famous models are described in their respective papers, you could reimplement them and train them on ImageNet. Fortunately, their code is often released on Github by the authors or reimplemented by others. Most frameworks maintain model zoos of the most popular networks. Some models also have pretrained weights available, mostly on ImageNet. Very useful for transfer learning (see later).

Overview website:

Caffe:

https://github.com/BVLC/caffe/wiki/Model-Zoo

Tensorflow:

https://github.com/tensorflow/models

Pytorch:

https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/torchvision/models.html

Papers with code:

Several criteria have to be considered when choosing an architecture:

Accuracy on ImageNet.

Number of parameters (RAM consumption).

Speed (flops).

Fig. 3.66 Speed-accuracy trade-off of state-of-the-art CNNs. Source: https://dataconomy.com/2017/04/history-neural-networks¶

3.3. Applications of CNN¶

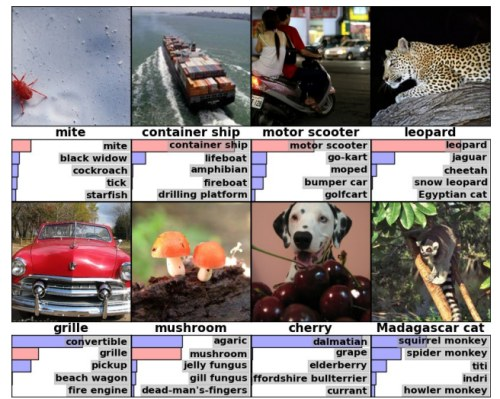

3.3.1. Object recognition¶

Object recognition has become very easy thanks to CNNs. In object recognition, each image is associated to a label. With huge datasets like ImageNet (14 millions images), a CNN can learn to recognize 1000 classes of objects with a better accuracy than humans. Just get enough examples of an object and it can be recognized.

Fig. 3.67 Object recognition on ImageNet. Source [Krizhevsky et al., 2012].¶

3.3.2. Facial recognition¶

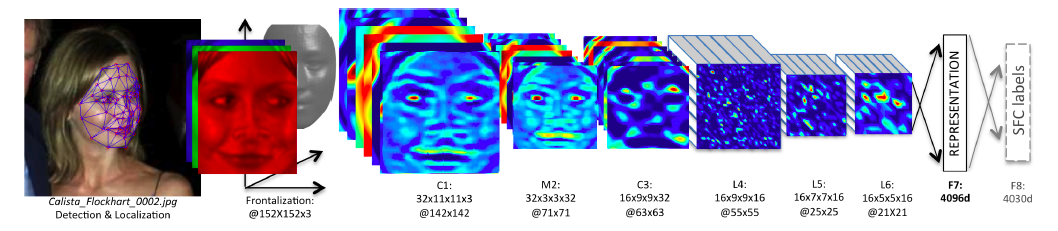

Facebook used 4.4 million annotated faces from 4030 users to train DeepFace [Taigman et al., 2014]. Accuracy of 97.35% for recognizing faces, on par with humans. Used now to recognize new faces from single examples (transfer learning, one-shot learning).

Fig. 3.68 DeepFace. Source [Taigman et al., 2014].¶

3.3.3. Pose estimation¶

PoseNet [Kendall et al., 2016] is a Inception-based CNN able to predict 3D information from 2D images. It can be for example the calibration matrix of a camera, 3D coordinates of joints or facial features. There is a free tensorflow.js implementation that can be used in the browser.

Fig. 3.69 PoseNet [Kendall et al., 2016]. Source: https://blog.tensorflow.org/2019/01/tensorflow-lite-now-faster-with-mobile.html¶

3.3.4. Speech recognition¶

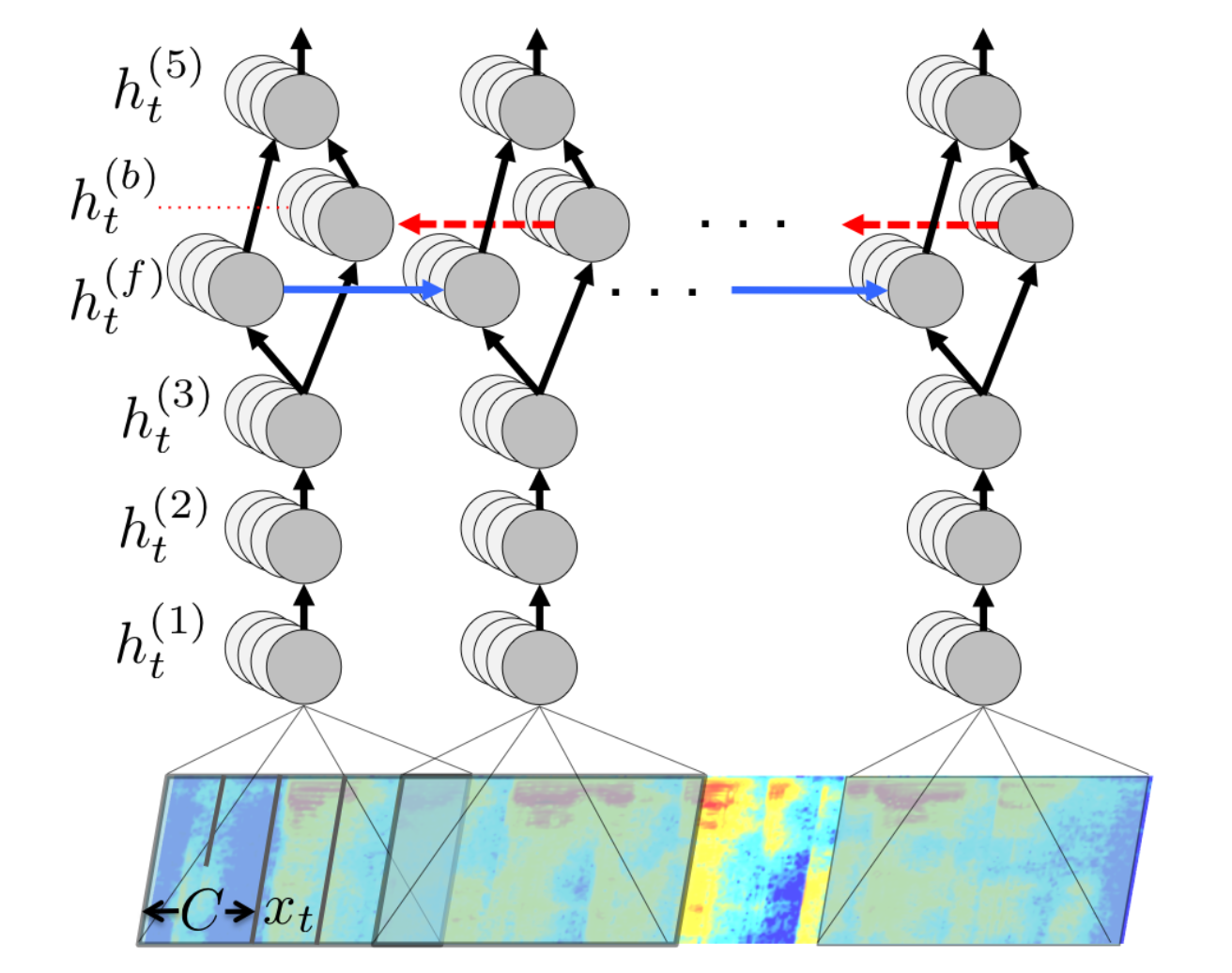

To perform speech recognition, one could treat speech signals like images: one direction is time, the other are frequencies (e.g. mel spectrum). A CNN can learn to associate phonemes to the corresponding signal. DeepSpeech [Hannun et al., 2014] from Baidu is one of the state-of-the-art approaches. Convolutional networks can be used on any signals where early features are local. It uses additionally recurrent networks, which we will see later.

Fig. 3.70 DeepSpeech. Source [Hannun et al., 2014].¶

3.3.5. Sentiment analysis¶

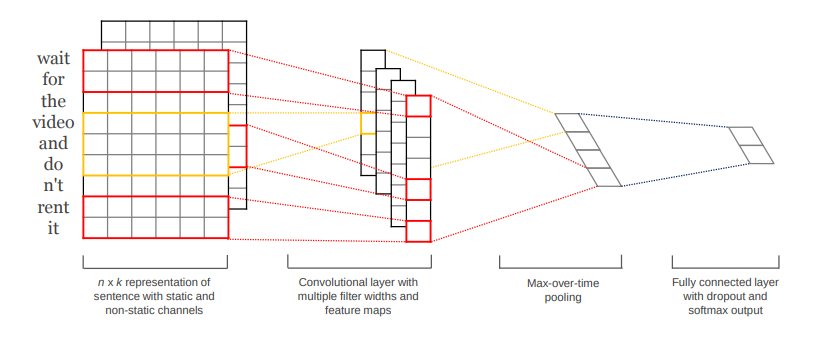

It is also possible to apply convolutions on text. Sentiment analysis assigns a positive or negative judgment to sentences. Each word is represented by a vector of values (word2vec). The convolutional layer can slide over all over words to find out the sentiment of the sentence.

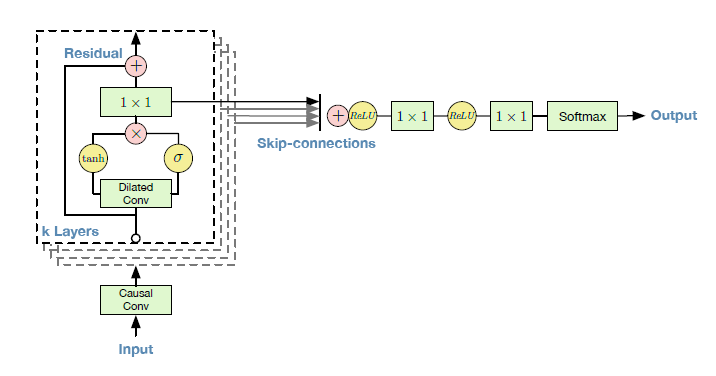

3.3.6. Wavenet : text-to-speech synthesis¶

Text-To-Speech (TTS) is also possible using CNNs. Google Home relies on Wavenet [Oord et al., 2016], a complex CNN using dilated convolutions to grasp long-term dependencies.

Fig. 3.72 Wavenet [Oord et al., 2016]. Source: https://deepmind.com/blog/wavenet-generative-model-raw-audio/¶

Fig. 3.73 Dilated convolutions in Wavenet [Oord et al., 2016]. Source: https://deepmind.com/blog/wavenet-generative-model-raw-audio/¶

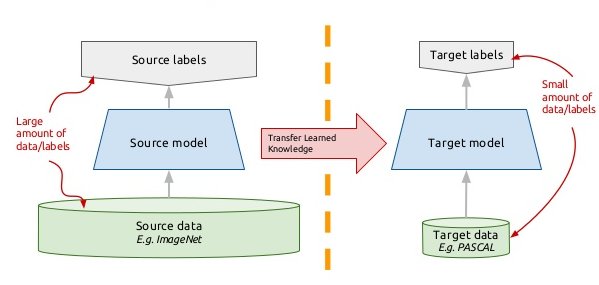

3.4. Transfer learning¶

Myth: ones needs at least one million labeled examples to use deep learning. This is true if you train the CNN end-to-end with randomly initialized weights. But there are alternatives:

Unsupervised learning (autoencoders) may help extract useful representations using only images.

Transfer learning allows to re-use weights obtained from a related task/domain.

Fig. 3.74 Transfer learning. Source: http://imatge-upc.github.io/telecombcn-2016-dlcv¶

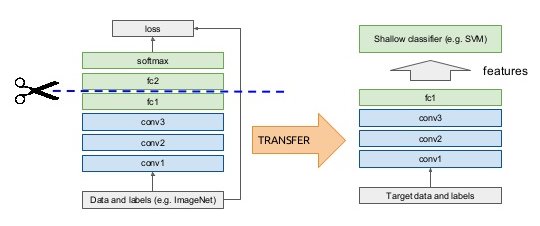

Take a classical network (VGG-16, Inception, ResNet, etc.) trained on ImageNet (if your task is object recognition).

Off-the-shelf

Cut the network before the last layer and use directly the high-level feature representation.

Use a shallow classifier directly on these representations (not obligatorily NN).

Fig. 3.75 Off-the-shelf transfer learning. Source: http://imatge-upc.github.io/telecombcn-2016-dlcv¶

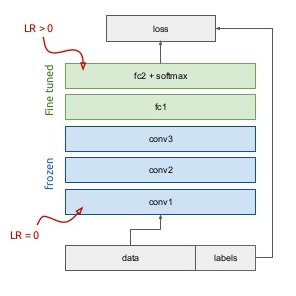

Fine-tuning

Use the trained weights as initial weight values and re-train the network on your data (often only the last layers, the early ones are frozen).

Fig. 3.76 Fine-tuned transfer learning. Source: http://imatge-upc.github.io/telecombcn-2016-dlcv¶

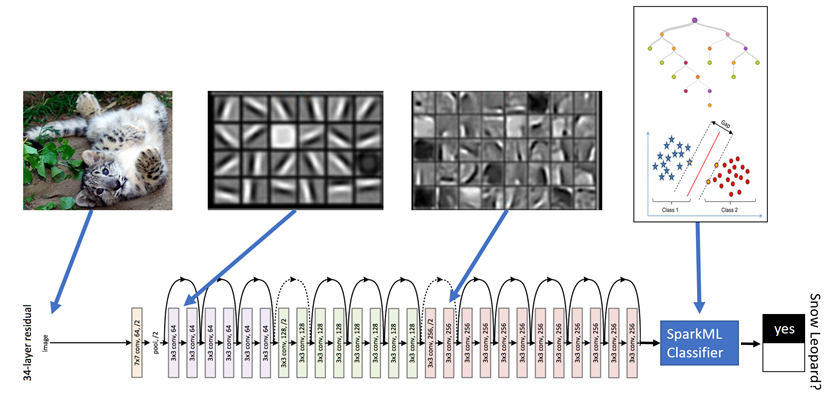

Example of transfer learning

Microsoft wanted a system to automatically detect snow leopards into the wild, but there were not enough labelled images to train a deep network end-to-end. They used a pretrained ResNet50 as a feature extractor for a simple logistic regression classifier.

Transfer learning in keras

Keras provides pre-trained CNNs that can be used as feature extractors:

from tf.keras.applications.vgg16 import VGG16

# Download VGG without the FC layers

model = VGG16(include_top=False,

input_shape=(300, 300, 3))

# Freeze learning in VGG16

for layer in model.layers:

layer.trainable = False

# Add a fresh MLP on top

flat1 = Flatten()(model.layers[-1].output)

class1 = Dense(1024, activation='relu')(flat1)

output = Dense(10, activation='softmax')(class1)

# New model

model = Model(

inputs=model.inputs, outputs=output)

See https://keras.io/api/applications/ for the full list of pretrained networks.

3.5. Ensemble learning¶

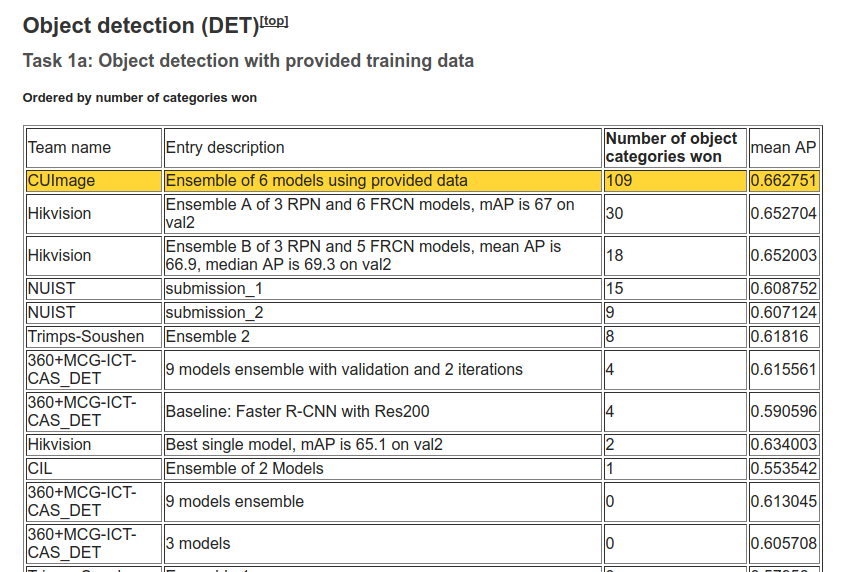

Since 2016, only ensembles of existing networks win the competitions.

Fig. 3.77 Top networks on the ImageNet 2016 competition. Source http://image-net.org/challenges/LSVRC/2016/results¶

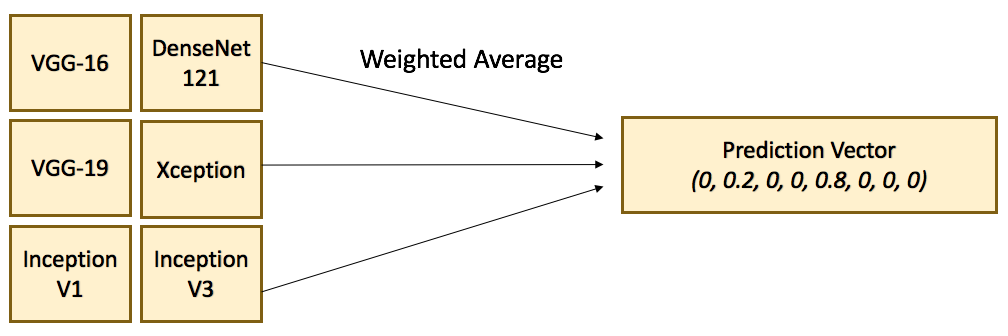

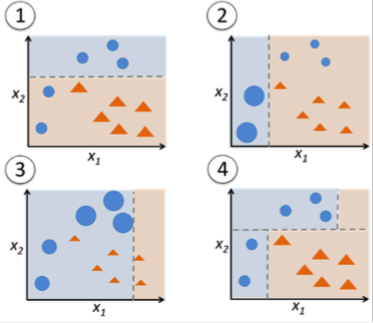

Ensemble learning is the process of combining multiple independent classifiers together, in order to obtain a better performance. As long the individual classifiers do not make mistakes for the same examples, a simple majority vote might be enough to get better approximations.

Fig. 3.78 Ensemble of pre-trained CNNs. Source https://flyyufelix.github.io/2017/04/16/kaggle-nature-conservancy.html¶

Let’s consider we have three independent binary classifiers, each with an accuracy of 70% (P = 0.7 of being correct). When using a majority vote, we get the following cases:

all three models are correct:

P = 0.7 * 0.7 * 0.7 = 0.3492

two models are correct

P = (0.7 * 0.7 * 0.3) + (0.7 * 0.3 * 0.7) + (0.3 * 0.7 * 0.7) = 0.4409

two models are wrong

P = (0.3 * 0.3 * 0.7) + (0.3 * 0.7 * 0.3) + (0.7 * 0.3 * 0.3) = 0.189

all three models are wrong

P = 0.3 * 0.3 * 0.3 = 0.027

The majority vote is correct with a probability of P = 0.3492 + 0.4409 = 0.78 ! The individual learners only have to be slightly better than chance, but they must be as independent as possible.

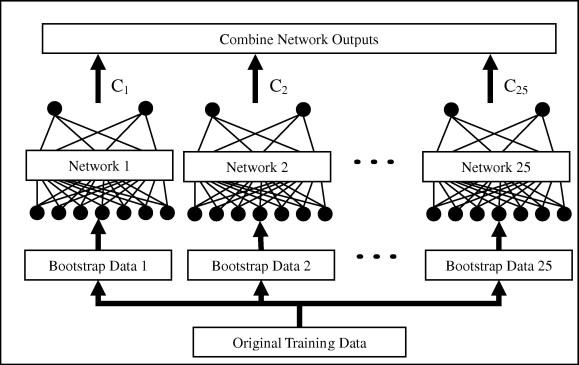

3.5.1. Bagging¶

Bagging methods (bootstrap aggregation) trains multiple classifiers on randomly sampled subsets of the data. A random forest is for example a bagging method for decision trees, where the data and features are sampled.. One can use majority vote, unweighted average, weighted average or even a meta-learner to form the final decision.

Fig. 3.79 Bagging. Source: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0957417409008781¶

3.5.2. Boosting¶

Bagging algorithms aim to reduce the complexity of models that overfit the training data. Boosting is an approach to increase the complexity of models that suffer from high bias, that is, models that underfit the training data. Algorithms: Adaboost, XGBoost (gradient boosting)…

Fig. 3.80 Boosting. Source: https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2015/11/quick-introduction-boosting-algorithms-machine-learning/¶

Boosting is not very useful with deep networks (overfitting), but there are some approaches like SelfieBoost (https://arxiv.org/pdf/1411.3436.pdf).

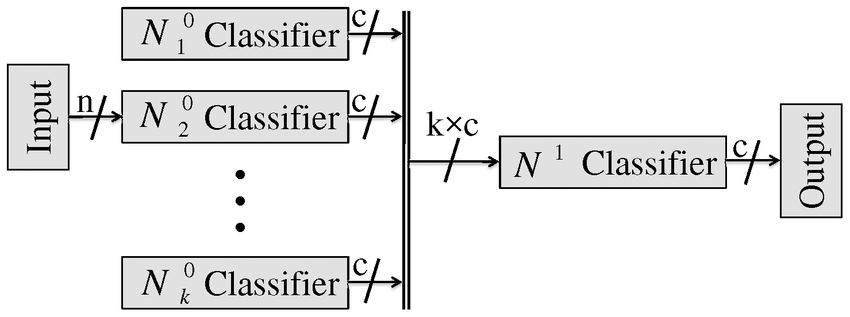

3.5.3. Stacking¶

Stacking is an ensemble learning technique that combines multiple models via a meta-classifier. The meta-model is trained on the outputs of the basic models as features. Winning approach of ImageNet 2016 and 2017. See https://blog.statsbot.co/ensemble-learning-d1dcd548e936

Fig. 3.81 Stacking. Source: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024386.g005¶